Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > Epidemiol Health > Volume 45; 2023 > Article

-

COVID-19

Original Article

Lack of compensation for COVID-19-related overtime work and its association with burnout among EMS providers in Korea -

Ji-Hwan Kim1

, Jaehong Yoon2,3

, Jaehong Yoon2,3 , Soo Jin Kim4

, Soo Jin Kim4 , Ja Young Kim1

, Ja Young Kim1 , Jinwook Bahk5

, Jinwook Bahk5 , Seung-Sup Kim1,6

, Seung-Sup Kim1,6

-

Epidemiol Health 2023;45:e2023058.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4178/epih.e2023058

Published online: June 15, 2023

1Department of Environmental Health Sciences, Graduate School of Public Health, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea

2Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea

3National Traffic Injury Rehabilitation Research Institute, National Traffic Injury Rehabilitation Hospital, Yangpyeong, Korea

4Fire Science Research Center, Seoul Metropolitan Fire Service Academy, Seoul, Korea

5Department of Public Health, Keimyung University, Daegu, Korea

6Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA

- Correspondence: Seung-Sup Kim Department of Environmental Health Sciences, Graduate School of Public Health, Seoul National University, 1 Gwanak-ro, Gwanak-gu, Seoul 08826, Korea E-mail: kim.seungsup@snu.ac.kr

© 2023, Korean Society of Epidemiology

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Abstract

-

OBJECTIVES

- This study examined the association between lack of compensation for COVID-19-related overtime work (LCCOW) and burnout among emergency medical service (EMS) providers in Seoul, Korea.

-

METHODS

- We conducted a cross-sectional survey of 693 EMS providers in Seoul, Korea. Participants were classified into 3 groups according to their experience of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related overtime work and LCCOW: (1) “did not experience,” (2) “experienced and was compensated,” and (3) “experienced and was not compensated.” Burnout was measured using the Korean version of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory, which has 3 subdomains: personal burnout (PB), work-related burnout (WRB), and citizen-related burnout (CRB). Multiple linear regression was applied to examine whether LCCOW was associated with burnout after adjusting for potential confounders.

-

RESULTS

- In total, 74.2% of participants experienced COVID-19-related overtime work, and 14.6% of those who worked overtime experienced LCCOW. COVID-19-related overtime work showed a statistically non-significant association with burnout. However, the association differed by LCCOW. Compared to the “did not experience” group, the “experienced and was not compensated” group was associated with PB (β=10.519; 95% confidence interval [CI], 3.455 to 17.584), WRB (β=10.339; 95% CI, 3.398 to 17.280), and CRB (β=12.290; 95% CI, 6.900 to 17.680), whereas no association was observed for the “experienced and was compensated” group. Furthermore, an analysis restricted to EMS providers who worked overtime due to COVID-19 showed that LCCOW was associated with PB (β=7.970; 95% CI, 1.064 to 14.876), WRB (β=7.276; 95% CI, 0.270 to 14.283), and CRB (β=10.000; 95% CI, 3.435 to 16.565).

-

CONCLUSIONS

- This study suggests that LCCOW could be critical in worsening burnout among EMS providers who worked overtime due to COVID-19.

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), which has caused numerous deaths and suffering worldwide, has also negatively influenced the work environment of healthcare workers [1]. Existing studies have reported that healthcare workers, including medical specialists, nurses, and care workers, are at high risk of being exposed to and contracting COVID-19 [2,3]. Emergency medical services (EMS) providers could be especially vulnerable to COVID-19, given the possibility of prolonged face-to-face contact with patients and increased exposure to infectious aerosols [4].

- In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, increased workloads have induced frequent overtime work among healthcare workers [5-8]. For example, research in China found that 54% of healthcare workers experienced overtime work during the COVID-19 pandemic [9]. A study in Australia found that 52.2% of pharmacists had worked overtime due to COVID-19 [10]. Furthermore, a study in Germany found that healthcare workers who worked in COVID-19-related environments reported more overtime hours than those who did not [3].

- A growing body of evidence has found that overtime work could harm workers’ mental health [5,11-14]. For example, a study of Japanese workers found that those with longer overtime work showed a higher risk of anxiety, fatigue, and depression than those who worked overtime 20 hours or fewer per month [15]. Also, a few studies found that working overtime during the COVID-19 pandemic could be related to a higher risk of burnout among healthcare workers [9,16]. Considering that burnout among healthcare workers is associated with work performance [17], COVID-19-related overtime work among EMS providers and related mental health outcomes could present public health concerns [18].

- Furthermore, several studies have focused on the role of compensation in the association between overtime work and health [19-24]. Suggested compensation for overtime work includes financial compensation (e.g., extra payment) [19-24] and extra rest time (e.g., time off) [20,22,24]. For example, a study of Swedish physicians reported that unpaid overtime was associated with a high level of stress [23]. A cross-sectional survey of physicians in Spain also found that financial compensation for overtime work was related to a lower risk of burnout [19].

- In Korea, EMS providers have been responsible for transporting patients who may have COVID-19 during the COVID-19 pandemic [25]. As part of their COVID-19-related work, EMS providers were required to undertake additional tasks, including wearing personal protective equipment, pre-identifying symptoms related to COVID-19, and disinfecting ambulances before returning to the fire department [26]. These work burdens have increased the hours spent on EMS activities [25], which could result in overtime work.

- However, few studies have explored the prevalence of overtime work and its potential relationship to health conditions among EMS providers during the COVID-19 pandemic [19]. Considering that all EMS providers in Korea are public officers and responsible for the health and safety of citizens, it is also necessary to investigate the role of organizational factors in the association between overtime work and mental health problems among EMS providers. Therefore, this study analyzed data from EMS providers in Seoul, Korea to answer the following questions:

- (1) Is there an association between COVID-19-related overtime work and burnout among Korean EMS providers? Does the association differ by lack of compensation for COVID-19-related overtime work (LCCOW)?

- (2) Is there an association between LCCOW and burnout among Korean EMS providers who worked overtime due to COVID-19?

INTRODUCTION

- Study population

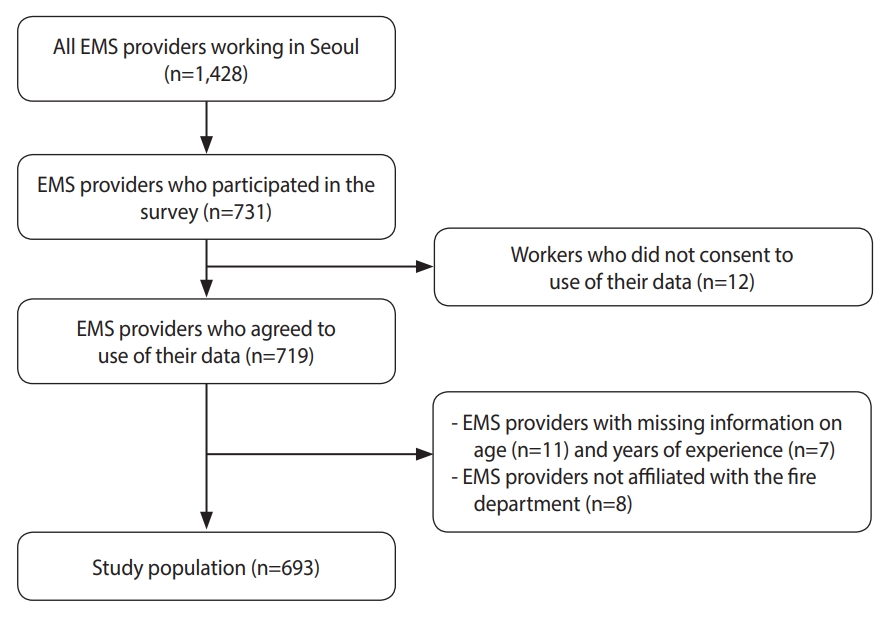

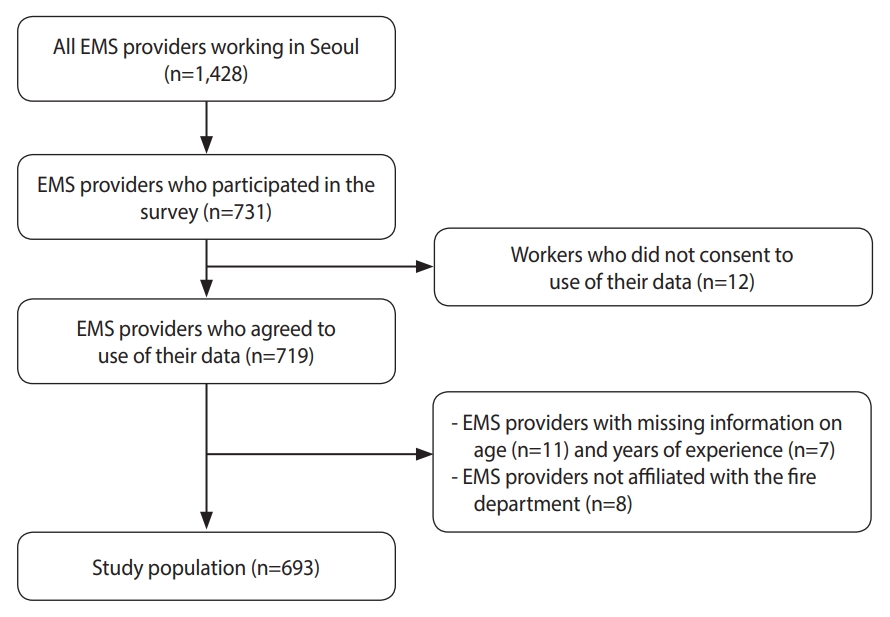

- In 2021, we conducted a cross-sectional survey with the Fire Science Research Center of Seoul Metropolitan Fire Service Academy to investigate the COVID-19-related work environment and health status among EMS providers in Seoul, Korea. Data were collected through an online survey system of Seoul from June 9, 2021 to June 28, 2021. Informed consent was obtained after respondents were provided with an explanation of the research and asked about their willingness to participate. The target population was all EMS providers working in Seoul (n=1,428). Approximately 51% (n=731) of EMS providers participated in the survey. After excluding data from respondents who did not consent to the use of their data (n=12), who have missing information on age (n=11) and years of experience (n=7), and who were not affiliated with the fire department (n=8), the size of the study population was 693 (Figure 1).

- Measures

- The experience of COVID-19-related overtime work and LCCOW was measured through the question, “From January 2020 to the present, have you ever worked overtime due to the COVID-19 situation? If yes, have you ever not received adequate compensation (e.g., vacation or additional financial compensation) for the overtime work?” Respondents could answer (1) “did not experience overtime work” (“did not experience”), (2) “experienced overtime work, always received adequate compensation” (“experienced and was compensated”), and (3) “experienced overtime work, did not receive adequate compensation at least once” (“experienced and was not compensated”).

- Burnout was measured using the Korean version of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI) [27], initially developed by Kristensen et al. [28]. The CBI has 3 domains: personal burnout (PB), work-related burnout (WRB), and client-related burnout. PB indicates the degree of physical and psychological fatigue and exhaustion experienced by a person. WRB indicates the degree of physical and psychological fatigue and exhaustion that is perceived by a person as related to his/her work. Client-related burnout indicates the degree of physical and psychological fatigue and exhaustion that is perceived by a person as related to his/her work with clients. Considering the clients of EMS providers, the concept of client-related burnout was modified to citizen-related burnout (CRB). Each domain consists of 6 items, 7 items, and 6 items, respectively. All items were assessed on a 5-point Likert scale and were scored from 0 to 100 (always/to a very high degree=100, often/to a high degree=75, sometimes/somewhat=50, seldom/to a low degree=25, and never/almost never/to a very low degree=0). The fourth item for WRB was reverse-coded because it measured a positive concept. The average score was calculated for each of the 3 domains, and the scoring range was 0 to 100 per domain. Higher scores indicated a higher degree of burnout. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.938 for PB, 0.913 for WRB, and 0.925 for CRB.

- As potential confounders, 5 variables were selected: age, sex, household size, job rank, and years of experience. Age was classified into 4 categories (21-30, 31-35, 36-40, and 41-60 years old). All respondents were categorized as male or female. Household size was grouped into 4 categories (1, 2, 3, or ≥ 4 people). Job rank was classified into 4 categories (sobang-sa, sobang-gyo, sobang-jang, sobang-wi or higher). Years of experience was coded into 4 categories (< 5, 5-9, 10-14, ≥ 15 years).

- Additionally, COVID-19-related workload variables were measured for the period from January 2020 until the survey. Yes/no questions were used to measure several experiences: receiving COVID-19 screening test, COVID-19-related self-quarantine, COVID-19 infection, and not going home after work because of fear of transmitting COVID-19 to the family. A perceived increase in workload after the outbreak of COVID-19 compared to 2019 was also measured by a yes/no question. The experience of lack of time for administrative work due to an increase in fieldwork, difficulty in selecting a hospital to transfer a patient, transferring the patient to the outside of service area, and waiting more than an hour after transferring the patient to the hospital were measured and classified into 2 categories: no (“no” and “not applicable”) and yes (yes).

- Statistical analysis

- A multiple linear regression model was applied to investigate the role of LCCOW in the association between COVID-19-related overtime work and burnout among EMS providers, after adjusting for confounders. Since burnout and COVID-19-related overtime work among EMS providers from the same fire department could be correlated, cluster-robust standard errors were applied using information about participants’ affiliated fire departments. All confounders were included as categorical variables in the analysis. Results were presented as coefficients with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All statistical analyses were performed with Stata/SE version 17.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA).

- Ethics statement

- This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Korea University (KUIRB-2021-0163-01).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

- Table 1 shows the distribution of the study population and the experience of COVID-19-related overtime work by each covariate. Overall, 74.2% (n=514) of the study population reported that they experienced COVID-19-related overtime work. Experience of COVID-19-related overtime work was prevalent among EMS providers who were aged 31-35 years old, had fewer years of experience, and had a lower job rank. Also, the prevalence of COVID-19-related overtime work was higher among EMS providers with COVID-19-related workloads, including the experience of difficulty of selecting a hospital to transfer a patient (Supplementary Material 1). The prevalence of LCCOW among those who worked overtime did not differ by the characteristics of the study population, including COVID-19-related workload (Supplementary Material 2). The average burnout score was higher among EMS providers who were female, lived in a 2-person household, had 5-9 years of experience, held the sobang-gyo rank, and had a COVID-19-related workload (Supplementary Material 3).

- Experience of COVID-19-related overtime work showed a statistically non-significant association with burnout (Table 2). However, after being stratified by LCCOW, statistically significantly higher scores of PB (β=10.519; 95% CI, 3.455 to 17.584), WRB (β=10.339; 95% CI, 3.398 to 17.280), and CRB (β=12.290; 95% CI, 6.900 to 17.680) were observed among the “experienced and was not compensated” group when compared to the “did not experience” group, though not among the “experienced and was compensated” group (Table 2).

- We also conducted an analysis restricted to EMS providers who had worked overtime due to COVID-19 (Table 3). LCCOW was significantly associated with burnout among EMS providers after adjusting for confounders, including COVID-19-related workload. Compared to the “experienced and was compensated” group, the “experienced and was not compensated” group showed higher scores for PB (β=7.970; 95% CI, 1.064 to 14.876), WRB (β=7.276; 95% CI, 0.270 to 14.283), and CRB (β=10.000; 95% CI, 3.435 to 16.565).

RESULTS

- This study found that approximately 75% of EMS providers in Seoul experienced COVID-19-related overtime work from January 2020 to June 2021, and about 15% of EMS providers who worked overtime experienced LCCOW. The burden of overtime work during the COVID-19 pandemic could constitute a public health concern, considering potential long-term effects on the health of EMS providers [29]. This study also showed that the average burnout score of EMS providers in Seoul was above 50, which could indicate a high level of burnout [27]. A high level of burnout among EMS providers is a public health concern because it could lead to turnover intention and decreased work performance, which would increase the burden on the healthcare system [30,31].

- Our findings suggest that overtime was not associated with burnout among EMS providers, which is inconsistent with previous studies [32,33]. Notably, however, we found that compensation might play a critical role in the association between COVID-19-related overtime work and burnout among EMS providers, which is consistent with a study of German workers [34]. A statistically significantly higher degree of burnout was observed among EMS providers who did not receive adequate compensation for COVID-19-related overtime work than among those who did not work overtime. We also found that LCCOW was related to burnout among EMS providers who worked overtime even after adjusting for COVID-19-related workload.

- There could be several explanations for our results, considering the examples of compensation for COVID-19-related overtime work indicated in our questionnaire (e.g., vacation, additional financial compensation). First, it is possible that the EMS providers who worked overtime did not receive enough time to recover from fatigue. A study of German workers found that boundaryless working hours, including overtime, could negatively influence workers’ states of recovery [35]. Second, an imbalance between financial/non-financial compensation and COVID-19-related overtime work might lead to higher burnout among EMS providers. Previous studies reported that a lack of rewards for workers’ efforts could lead to emotional distress [36] and work dissatisfaction [24]. Therefore, LCCOW might imply an imbalance between EMS providers’ efforts, including overtime work, and rewards from the organization, including vacation, additional financial compensation, and promotion, which could increase the risk of burnout among EMS providers [37-39].

- We also found a statistically non-significant difference in burnout scores between EMS providers who always received adequate compensation for COVID-19-related overtime work and those who did not work overtime. This result suggests that organizational rewards could reduce burnout among EMS providers who were required to engage in overtime work during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, we should interpret these results cautiously, in that EMS providers who did not work overtime also reported higher burnout than the levels observed among Korean workers before the COVID-19 pandemic [27]. Therefore, it is also necessary to explore the organizational factors (e.g., staffing adequacy) that could reduce burnout among Korean EMS providers.

- This study has several limitations. First, information on the temporal order between COVID-19-related overtime work and burnout could not be provided due to the cross-sectional design of the survey. Therefore, future longitudinal studies should adjust for potential confounders, including the degree of burnout at baseline. Second, there could be healthy worker survival effects. For example, EMS providers with severe burnout might have taken a leave of absence or resigned from their jobs, such that they did not participate in the survey. Excessive overtime work might also have prevented EMS providers from participating in the survey. Third, because a single question was used to assess COVID-19-related overtime work, the duration of overtime work could not be considered. Future studies should control for overtime work hours when examining the association between LCCOW and burnout. Fourth, the nature and magnitude of compensation for COVID-19-related overtime work were not measured. Future studies might investigate which types and what extent of compensation could buffer the impact of COVID-19-related overtime work on burnout among EMS providers, including the total hours of overtime work compensated and satisfaction with the corresponding amount of compensation.

- Using data from EMS providers in Seoul, this study showed that the association between overtime during the COVID-19 pandemic and burnout among EMS providers differed by LCCOW, and EMS providers who did not receive adequate compensation for overtime work had the highest burnout scores. LCCOW was also associated with burnout among EMS providers who worked overtime due to COVID-19. These findings imply that LCCOW could play a critical role in worsening burnout among EMS providers who worked overtime during the COVID-19 pandemic.

DISCUSSION

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplement Material 1.

Supplement Material 2.

Supplement Material 3.

-

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare for this study.

-

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (BK21 FOUR 5199990214126).

-

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conceptualization: Kim SS, Kim JH. Data curation: Kim SS, Kim JH, Yoon J, Kim SJ, Kim JY. Formal analysis: Kim JH. Funding acquisition: Kim SS, Kim JH. Writing – original draft: Kim JH. Writing – review & editing: Kim SS, Kim JH, Yoon J, Kim SJ, Kim JY, Bahk J.

NOTES

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

| Variables | Total | Experience of COVID-19-related overtime work | p-value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 693 (100) | 514 (74.2) | ||

| Sex | 0.123 | |||

| Male | 572 (82.5) | 431 (75.3) | ||

| Female | 121 (17.5) | 83 (68.6) | ||

| Age (yr) | <0.001 | |||

| 21-30 | 147 (21.2) | 110 (74.8) | ||

| 31-35 | 245 (35.4) | 206 (84.1) | ||

| 36-40 | 171 (24.7) | 111 (64.9) | ||

| 41-60 | 130 (18.8) | 87 (66.9) | ||

| Household size | 0.244 | |||

| One person | 133 (19.2) | 106 (79.7) | ||

| Two people | 155 (22.4) | 118 (76.1) | ||

| Three people | 178 (25.7) | 130 (73.0) | ||

| Four people or more | 227 (32.8) | 160 (70.5) | ||

| Years of experience (yr) | <0.001 | |||

| <5 | 266 (38.4) | 208 (78.2) | ||

| 5-9 | 219 (31.6) | 173 (79.0) | ||

| 10-14 | 111 (16.0) | 76 (68.5) | ||

| ≥15 | 97 (14.0) | 57 (58.8) | ||

| Job rank | 0.002 | |||

| Sobang-sa2 | 217 (31.3) | 174 (80.2) | ||

| Sobang-gyo | 287 (41.4) | 219 (76.3) | ||

| Sobang-jang | 140 (20.2) | 91 (65.0) | ||

| Sobang-wi or higher | 49 (7.1) | 30 (61.2) | ||

| COVID-19-related overtime work | Total | PB | WRB | CRB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did not experience | 179 (25.8) | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Experienced | 514 (74.2) | 2.495 (-2.332, 7.322) | 2.983 (-1.351, 7.316) | 3.128 (-0.079, 6.336) | |

| Stratified by LCCOW | |||||

| Did not experience | 179 (25.8) | Reference | Reference | Reference | |

| Experienced and was compensated | 439 (63.4) | 1.085 (-3.703, 5.872) | 1.690 (-2.540, 5.920) | 1.518 (-1.962, 4.999) | |

| Experienced and was not compensated | 75 (10.8) | 10.519 (3.455, 17.584)** | 10.339 (3.398, 17.280)** | 12.290 (6.900, 17.680)*** | |

Values are presented as number (%) or β (95% confidence interval).

LCCOW, lack of compensation for COVID-19-related overtime work; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; EMS, emergency medical services; PB, personal burnout; WRB, work-related burnout; CRB, citizen-related burnout.

1 Adjusted for age, sex, household size, job rank, and years of experience.

** p<0.01,

*** p<0.001.

| LCCOW | Total | PB | WRB | CRB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compensated | 439 (85.4) | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| Not compensated | 75 (14.6) | 7.970 (1.064, 14.876)* | 7.276 (0.270, 14.283)* | 10.000 (3.435, 16.565)** |

Values are presented as number (%) or β (95% confidence interval).

LCCOW, lack of compensation for COVID-19-related overtime work; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; EMS, emergency medical services; PB, personal burnout; WRB, work-related burnout; CRB, citizen-related burnout.

1 Adjusted for age, sex, household size, job rank, years of experience, and COVID-19-related workload.

* p<0.05,

** p<0.01.

- 1. Burdorf A, Porru F, Rugulies R. The COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic: consequences for occupational health. Scand J Work Environ Health 2020;46:229-230.ArticlePubMed

- 2. Lee J, Kim M. Estimation of the number of working population at high-risk of COVID-19 infection in Korea. Epidemiol Health 2020;42:e2020051.PubMedPMC

- 3. Kramer V, Papazova I, Thoma A, Kunz M, Falkai P, SchneiderAxmann T, et al. Subjective burden and perspectives of German healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2021;271:271-281.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 4. Carlsten C, Gulati M, Hines S, Rose C, Scott K, Tarlo SM, et al. COVID-19 as an occupational disease. Am J Ind Med 2021;64:227-237.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 5. Akman C, Cetin M, Toraman C. The analysis of emergency medicine professionals’ occupational anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic. Signa Vitae 2021;17:103-111.

- 6. Han S, Choi S, Cho SH, Lee J, Yun JY. Associations between the working experiences at frontline of COVID-19 pandemic and mental health of Korean public health doctors. BMC Psychiatry 2021;21:298.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 7. King R, Ryan T, Senek M, Wood E, Taylor B, Tod A, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on work, training and well-being experiences of nursing associates in England: a cross-sectional survey. Nurs Open 2022;9:1822-1831.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 8. Rodríguez-Rey R, Garrido-Hernansaiz H, Bueno-Guerra N. Working in the times of COVID-19. Psychological impact of the pandemic in frontline workers in Spain. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:8149.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. Zhang X, Jiang Y, Yu H, Jiang Y, Guan Q, Zhao W, et al. Psychological and occupational impact on healthcare workers and its associated factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in China. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2021;94:1441-1453.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 10. Johnston K, O’Reilly CL, Scholz B, Georgousopoulou EN, Mitchell I. Burnout and the challenges facing pharmacists during COVID-19: results of a national survey. Int J Clin Pharm 2021;43:716-725.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 11. Wang Q, Fan JY, Zhao HM, Liu YT, Xi XX, Kong LL, et al. A large scale of nurses participated in beating down COVID-19 in China: the physical and psychological distress. Curr Med Sci 2021;41:31-38.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 12. Watanabe M, Yamauchi K. The effect of quality of overtime work on nurses’ mental health and work engagement. J Nurs Manag 2018;26:679-688.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 13. Tomono M, Yamauchi T, Suka M, Yanagisawa H. Impact of overtime working and social interaction on the deterioration of mental well-being among full-time workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Japan: focusing on social isolation by household composition. J Occup Health 2021;63:e12254.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 14. Sato K, Kuroda S, Owan H. Mental health effects of long work hours, night and weekend work, and short rest periods. Soc Sci Med 2020;246:112774.ArticlePubMed

- 15. Kikuchi H, Odagiri Y, Ohya Y, Nakanishi Y, Shimomitsu T, Theorell T, et al. Association of overtime work hours with various stress responses in 59,021 Japanese workers: retrospective cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2020;15:e0229506.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 16. Kok N, van Gurp J, Teerenstra S, van der Hoeven H, Fuchs M, Hoedemaekers C, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 immediately increases burnout symptoms in ICU professionals: a longitudinal cohort study. Crit Care Med 2021;49:419-427.ArticlePubMed

- 17. Patel RS, Bachu R, Adikey A, Malik M, Shah M. Factors related to physician burnout and its consequences: a review. Behav Sci (Basel) 2018;8:98.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 18. Dall’Ora C, Ball J, Recio-Saucedo A, Griffiths P. Characteristics of shift work and their impact on employee performance and wellbeing: a literature review. Int J Nurs Stud 2016;57:12-27.ArticlePubMed

- 19. Macía-Rodríguez C, Alejandre de Oña Á, Martín-Iglesias D, Barrera-López L, Pérez-Sanz MT, Moreno-Diaz J, et al. Burn-out syndrome in Spanish internists during the COVID-19 outbreak and associated factors: a cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2021;11:e042966.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 20. Uman T, Broberg P, Tagesson T. Exploring the antecedents of the mental health of business professionals in Sweden. Work 2020;67:665-669.ArticlePubMed

- 21. Kevric J, Papa N, Perera M, Rashid P, Toshniwal S. Poor employment conditions adversely affect mental health outcomes among surgical trainees. J Surg Educ 2018;75:156-163.ArticlePubMed

- 22. Tsao L, Chang J, Ma L. Fatigue of Chinese railway employees and its influential factors: structural equation modelling. Appl Ergon 2017;62:131-141.ArticlePubMed

- 23. Tucker P, Bejerot E, Kecklund G, Aronsson G, Åkerstedt T. The impact of work time control on physicians’ sleep and well-being. Appl Ergon 2015;47:109-116.ArticlePubMed

- 24. Beckers DG, van der Linden D, Smulders PG, Kompier MA, Taris TW, Geurts SA. Voluntary or involuntary? Control over overtime and rewards for overtime in relation to fatigue and work satisfaction. Work Stress 2008;22:33-50.Article

- 25. Park JH, Song KJ, Shin SD, Hong KJ. The impact of COVID-19 pandemic on out-of-hospital cardiac arrest system-of-care: which survival chain factor contributed the most? Am J Emerg Med 2023;63:61-68.ArticlePubMed

- 26. Chung H, Namgung M, Lee DH, Choi YH, Bae SJ. Effect of delayed transport on clinical outcomes among patients with cardiac arrest during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Australas Emerg Care 2022;25:241-246.ArticlePubMed

- 27. Jeon GS, You SJ, Kim MG, Kim YM, Cho SI. Psychometric properties of the Korean version of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory in Korean homecare workers for older adults. PLoS One 2019;14:e0221323.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 28. Marra DE, Simons MU, Schwartz ES, Marston EA, Hoelzle JB. Burnt out: rate of burnout in neuropsychology survey respondents during the COVID-19 pandemic, brief communication. Arch Clin Neuropsychol 2023;38:258-263.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 29. Inoue Y, Yamamoto S, Stickley A, Kuwahara K, Miyamoto T, Nakagawa T, et al. Overtime work and the incidence of long-term sickness absence due to mental disorders: a prospective cohort study. J Epidemiol 2022;32:283-289.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 30. Krijgsheld M, Tummers LG, Scheepers FE. Job performance in healthcare: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2022;22:149.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 31. Poon YR, Lin YP, Griffiths P, Yong KK, Seah B, Liaw SY. A global overview of healthcare workers’ turnover intention amid COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review with future directions. Hum Resour Health 2022;20:70.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 32. Hino A, Inoue A, Kawakami N, Tsuno K, Tomioka K, Nakanishi M, et al. Buffering effects of job resources on the association of overtime work hours with psychological distress in Japanese white-collar workers. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2015;88:631-640.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 33. Ishida Y, Murayama H, Fukuda Y. Association between overtime-working environment and psychological distress among Japanese workers: a multilevel analysis. J Occup Environ Med 2020;62:641-646.PubMedPMC

- 34. Li J, Siegrist J. The role of compensation in explaining harmful effects of overtime work on self-reported heart disease: preliminary evidence from a Germany prospective cohort study. Am J Ind Med 2018;61:861-868.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 35. Vieten L, Wöhrmann AM, Michel A. Boundaryless working hours and recovery in Germany. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2022;95:275-292.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 36. Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol 1996;1:27-41.ArticlePubMed

- 37. Bakker AB, Killmer CH, Siegrist J, Schaufeli WB. Effort-reward imbalance and burnout among nurses. J Adv Nurs 2000;31:884-891.ArticlePubMed

- 38. Violanti JM, Mnatsakanova A, Andrew ME, Allison P, Gu JK, Fekedulegn D. Effort-reward imbalance and overcommitment at work: associations with police burnout. Police Q 2018;21:440-460.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 39. Padilla Fortunatti C, Palmeiro-Silva YK. Effort-reward imbalance and burnout among ICU nursing staff: a cross-sectional study. Nurs Res 2017;66:410-416.PubMed

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

- Effects of Post-COVID-19 Syndrome on Quality of Life Among Airline Crew

Jung-Ha Kim, Seunghye Choi

Workplace Health & Safety.2024;[Epub] CrossRef

KSE

KSE

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite